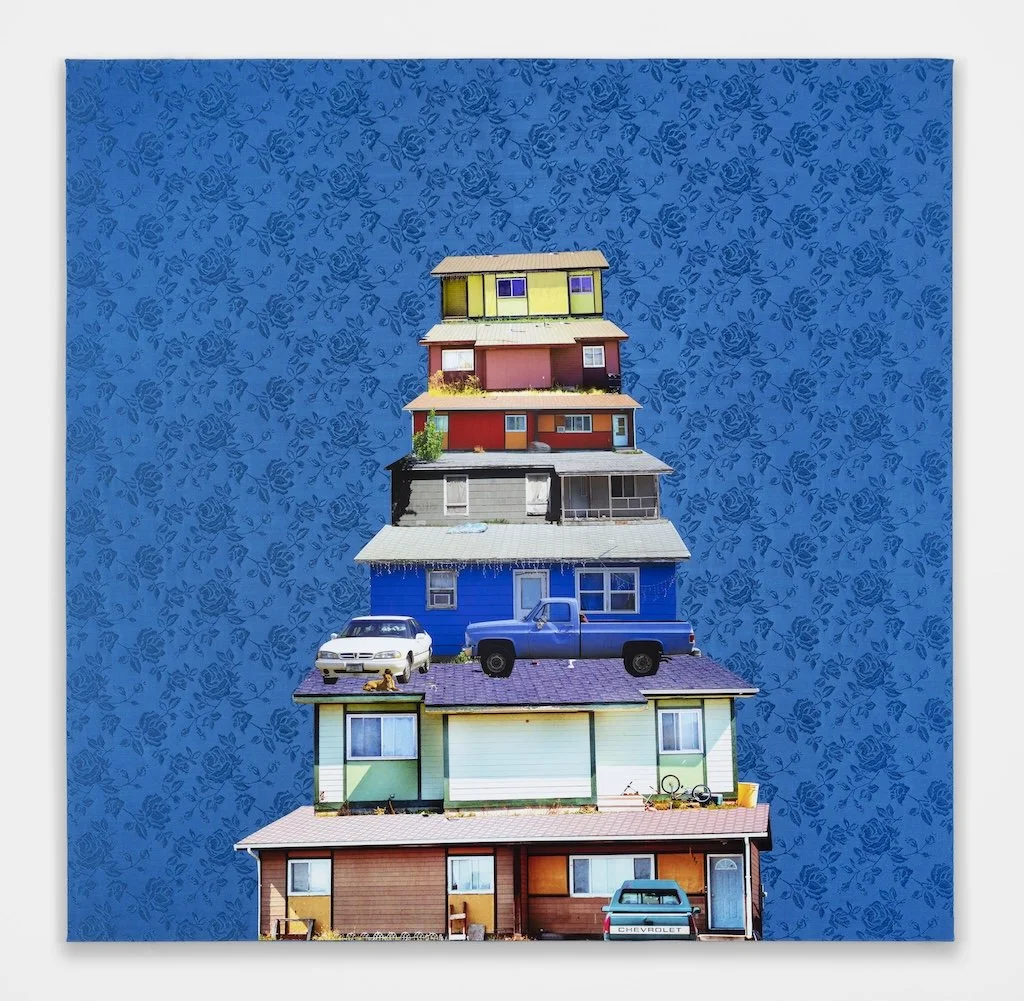

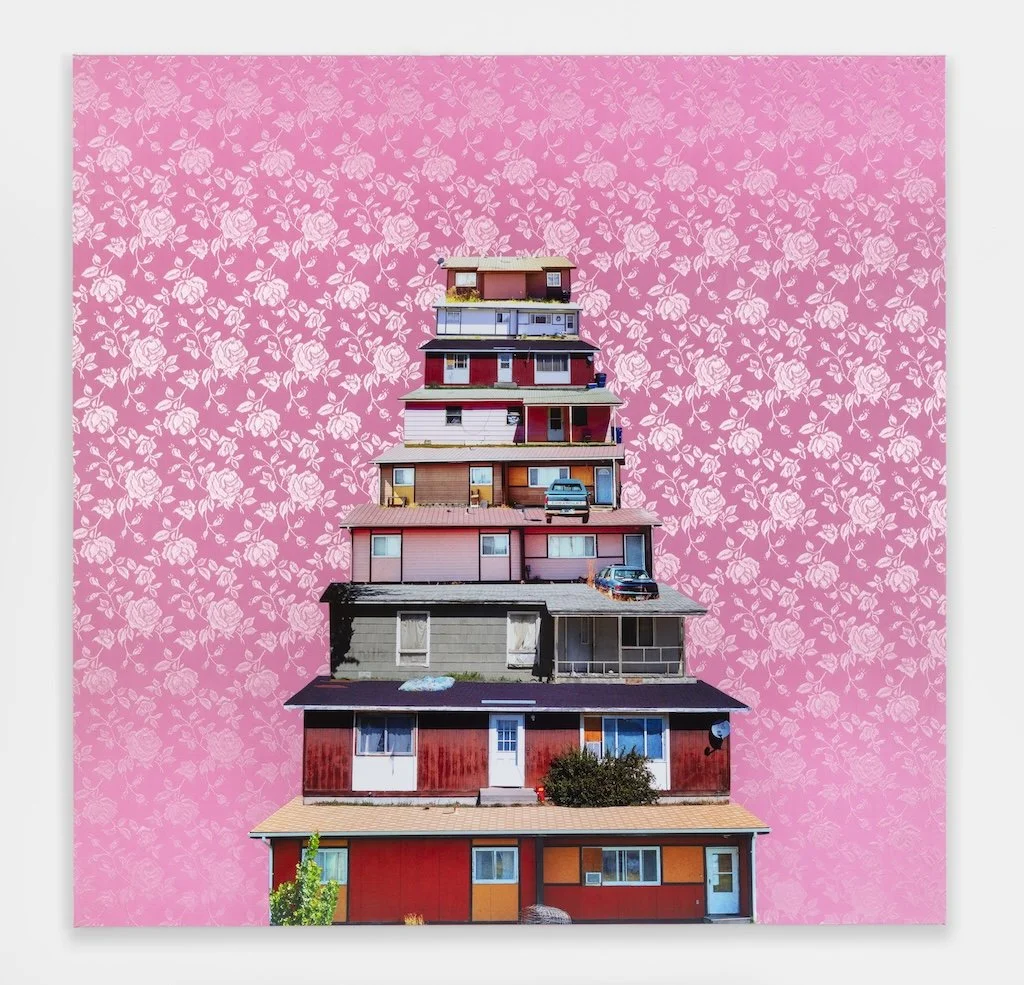

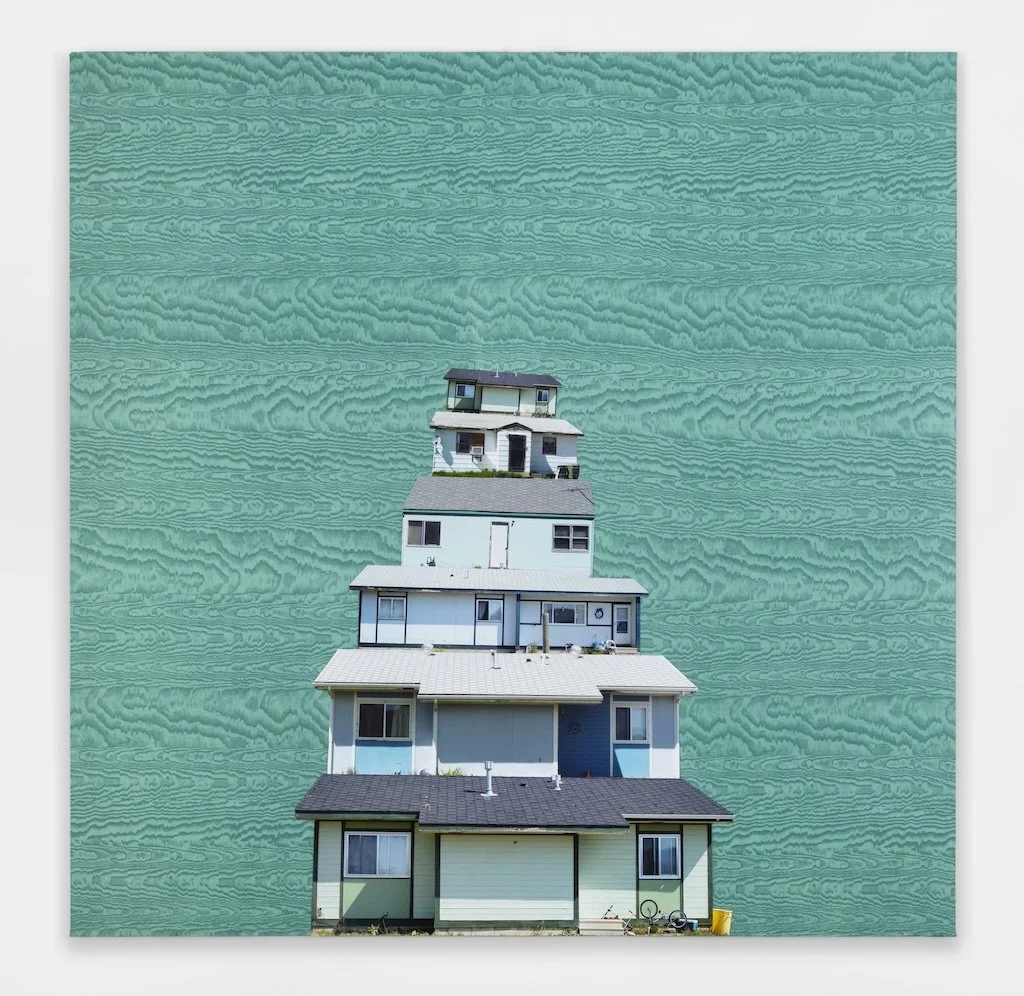

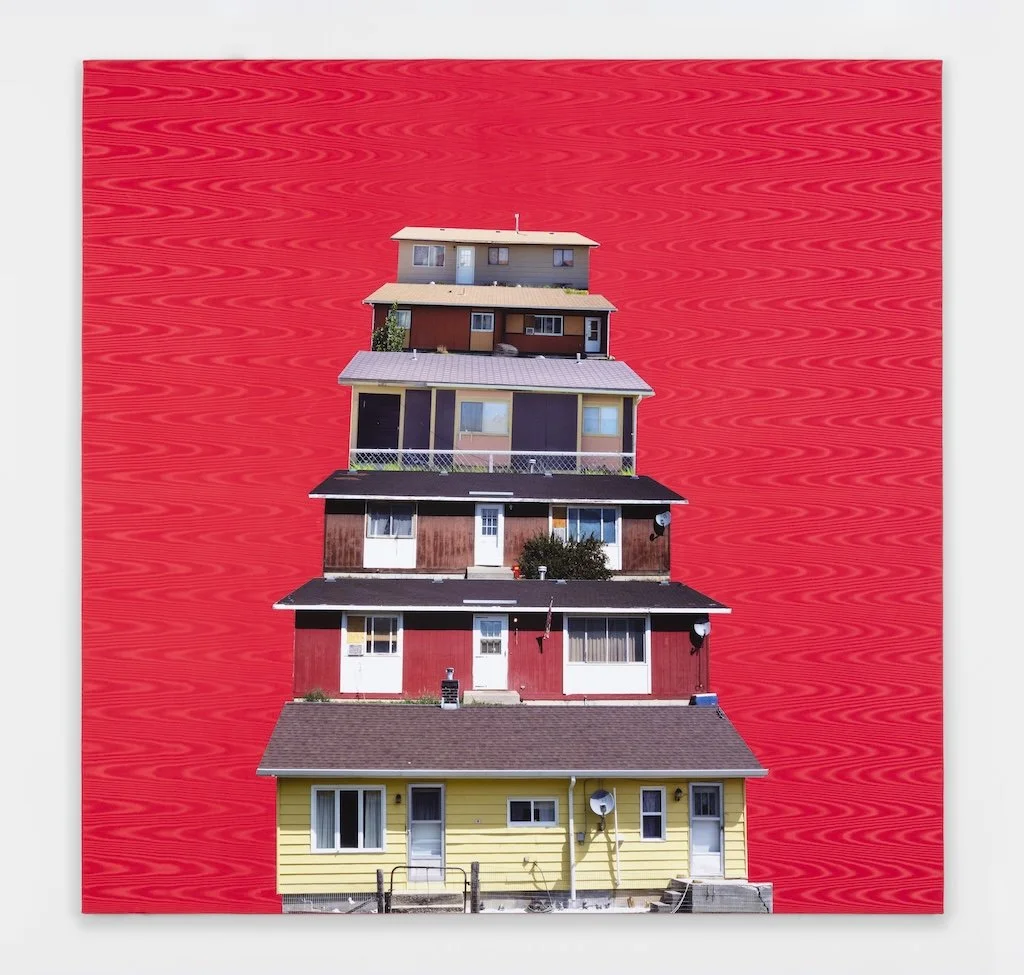

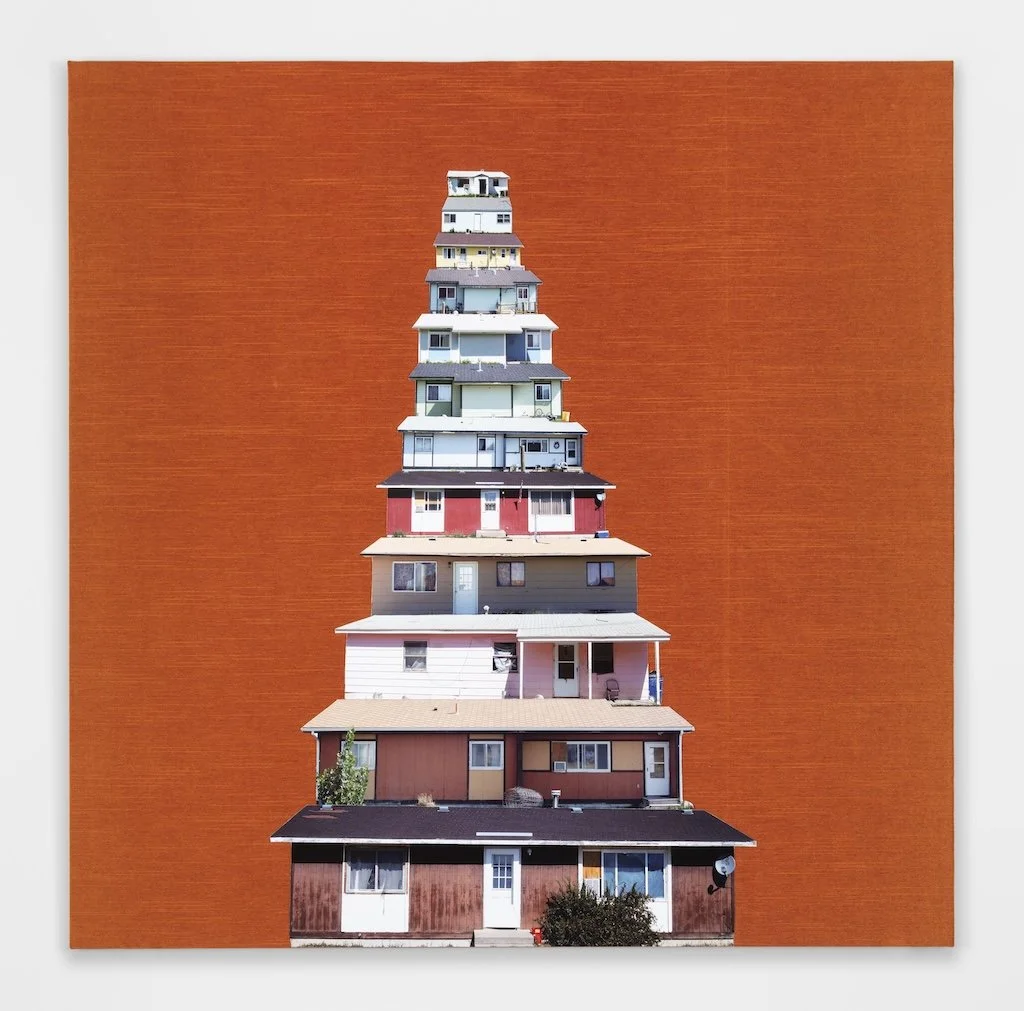

The (HUD)

The (HUD) 1, 2026

The (HUD) 2, 2026

The (HUD) 3, 2026

The (HUD) 5

The (HUD) 7

The (HUD) 4, 2026

The (HUD) 6

The (HUD) 8

The (HUD), 2026

Archival pigment print collages on fabric

36 x 36 inches

Photography by Kevin McConnell

Text by Cynthia Gladen

Single, cut-out images of objects draw the eye first to their color and shape, and then to the arresting contrast with their matte colors. These are familiar objects broken down to their basic, two-dimensional representations and made both alluring and disconcerting by the imperfection of the objects themselves, their unusual colors, so saturated and strange.

One could be forgiven for making the visual connection between Andy Warhol’s candy-colored pop art prints of both the ordinary and the famous and Wendy Red Star’s rez cars and houses series, shot in the brilliant Montana light in the summers of 2007 and 2008. The cars and especially the homes—cobalt, burnt orange, peach, flamingo pink, gold—are mounted on colored satin, evocative of a late 1970s suburban interior decorating aesthetic. The visual connection to Warhol’s sometimes garish color choices belies the truth of the rez homes: the rez home colors were not chosen by their occupants, or by the artist, but rather by the U.S. Government. They were, in fact, imposed colors. One could argue that neither did Warhol’s subjects/objects choose their own palettes—Warhol did—but Warhol’s colors weren’t selected because they were the least common denominator. Wendy Red Star’s father speculated that the colors of the houses were the result of the government buying the cheapest paint available, thus the motley palette, found nowhere but there. These were cast-off colors, suitable only for rez homes, and applied in staccato fashion to each of the three architectural styles found on the rez. That the home’s occupants chose not to repaint them is itself a form of resistance, its own kind of agency, a refusal to assign value to the choice and not to expend effort undoing yet another imposition.

It is here that any connection to Pop Art and Warhol ends. Whereas Warhol created his pieces from a place of privilege—a white man living in New York City who could flaunt both his disdain and his awe for gore and celebrity—in contrast, as Red Star says, “These are my people. This is my community. This is my family, and these are their homes and lives.” The setting is rural, highly impoverished, stark, and is the lived material reality of some of the least-celebrated people in the U.S.

-

Frieze LA 2026

Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, CA